- Published on

Climate Change and the Vanishing Baseline of Memory

- Authors

- Name

- Shaun Hutchins

One of the greatest challenges in understanding climate change is that we cannot truly feel how the world used to be. Climate is lived, not remembered. The air we breathe, the temperatures we endure, the seasons we experience—all of these shape our perception of "normal." But our sense of normal is quietly shifting with each generation.

Living on Earth in the late 1800s felt vastly different than it does today. The world was cooler, the seasons more predictable, and extreme weather events far less common. But unless we’ve studied historical records or scientific reconstructions, we have no visceral understanding of what that world was like. We can't recall what a cooler planet felt like in our bones. We can only guess. Imagine trying to remember a smell you've never experienced, or a color you've never seen.

This gap between lived experience and historical reality may represent an overlooked psychological phenomenon—perhaps even a new cognitive bias. Unlike more visible or immediate threats, climate change works slowly, across years and decades. Each generation comes to accept the climate they grow up with as the baseline. It's called “shifting baseline syndrome,” and while it’s typically used in ecology or conservation biology, it applies powerfully here.

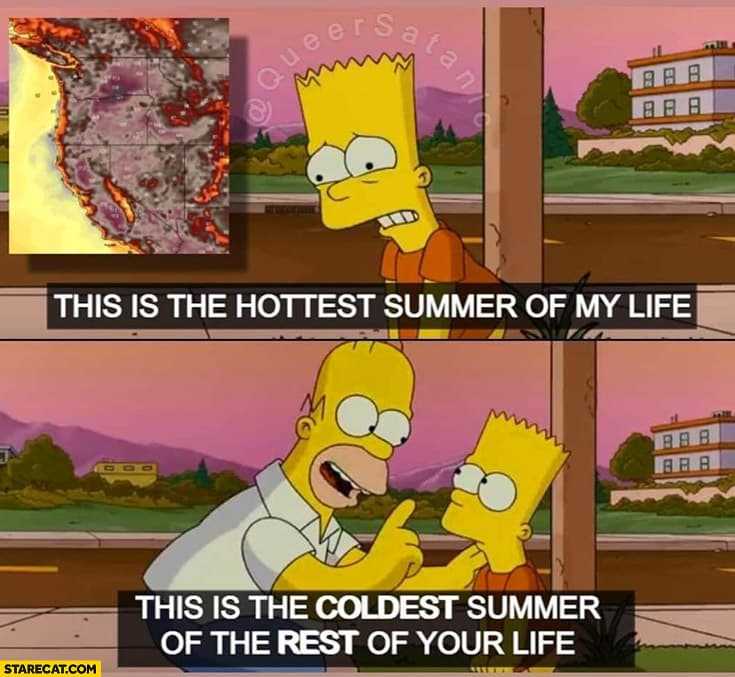

Children born in the last few years—during what have been the hottest years ever recorded—will grow up thinking of extreme heat as “normal.” They won't feel the loss of snow in places that used to see it every winter. They won’t miss the cool, crisp summers that once existed in regions now scorched by heatwaves. For them, the baseline of a changed planet will feel natural. And that presents a serious problem.

If we cannot feel the difference, it becomes harder to act on it. If we normalize extremes, we risk underreacting to them. And while public understanding of climate change has improved—fueled by science, media, and the visible impact of disasters—our collective response remains slow and tepid. There’s a growing cognitive dissonance between what we know intellectually and what we feel viscerally.

This isn't a call to despair, but a call for awareness. If part of the challenge of climate change is psychological, then part of the solution must be as well. We need to create shared narratives, intergenerational memory, and cultural touchstones that anchor us to the reality of change. We must resist accepting this new normal as unchangeable.

The Earth is heating—but our memory is fading. Let’s not forget how it used to feel. Because remembering may be a necessary step toward changing what comes next.